Courage and Cowardice - Chapter 19

“You… who are you?” Ulisses gasped. “Amaria, silly. Don’t you remember what the father said?” she laughed.

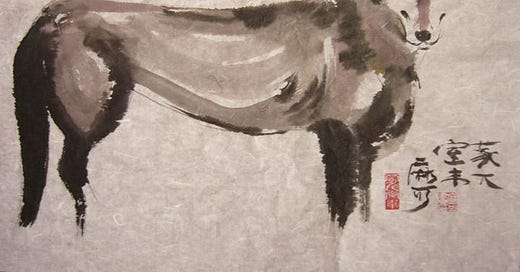

“And do you believe in the principle of universal love?” the wolf asked.

“Of course,” Mr. Dongguo replied.

And at that the wolf leapt upon the poor man, its fangs now glistening and dribbling with lustful hunger.

“Then in that case,” the wolf said. “You should allow me to eat you, for I am a wolf and dine solely on human flesh!”

-The Wolf of Zhongshan

“The jig was up, the game was lost, the trap had been set and poor old Compadre Coelho had been caught. The tar baby had done just what it was supposed to do, and there was nothing Compadre Coelho could do about it!”

The auntie wailed as the children around her began to weep. Oh, for Compadre Coelho to meet with such a terrible fate, it was simply too cruel! The children could not believe it was the end, but the auntie told the tale with such passion and soul that it was hard to contradict her.

“If only, Compadre Coelho thought, there was some way… And then, just like that, inspiration struck! As Comadre Raposa gaped her greedy, grinning fangs, Compadre Coelho began to wail.

“‘Oh please, please, please, Comadre Raposa!’ he cried. ‘Do with me what you like. Boil me, skin me, knock my head clean off if you must. But please, please don’t throw me in that there briar patch!’”

“‘Eh? Briar patch?’ Comadre Raposa glanced around until she saw the very thing. ‘Now there’s an idea!’”

Min-Na gazed into the morning sky from the balcony where she stood. There, in the east, the rising sun slowly lending more clarity as it made its skyward crawl, was the wall that separated Santama from the mainland. She could see it from here: Jianghu. When the sun reached its zenith, perhaps she could even see the domain the Yong clan had once ruled. She wondered how the new noble house that governed those lands was faring. No doubt the emperor had instated someone less scandalous, someone more suited to governing the new world the new dynasty was making.

Min-Na’s father had always claimed that their ancestor had met Prester John himself. This was unlikely, as many historians argued that Prester John was not one man, but an assigned title given to various missionaries and religious leaders across the centuries, but it made a good story, and it cemented the Yong family’s claim of legitimacy. After all, the Presterian Yeshuans had existed in Jianghu centuries before the Tartar horde had driven the Yong clan from their southern ancestral lands.

They had said it was for freedom. No more would the Tartars pick at each other like savage wolves, as the Jianghese lords laughed and looked on from their safely walled cities. They would unite, as one people, and vanquish the cruel, imperial masters who would have them dead or divided. The Yongs were among the first of the Jianghese to fall to the unified Tartar wave. Fleeing further and further north, the Yongs at last found peace near Canton. And when the Tartars finally took the imperial capital, the clan made plans for a final stand. With the océan to their backs, there was nowhere north to flee. So, they resolved to find either glory or death in the land where they had made a new home.

However, to the surprise of the Yong clan, when at last the Tartars reached Canton, they had little interest in supplanting them. The Tartar wolf had gobbled up many people on its northward trek, and had subsequently become bloated with cosmopolitanism. The new Khan believed a kingdom of many people should allow those people their ways. And though the Yongs were Jianghese, they were also Yeshuan, a faith that had a home with many of the Khan’s family and advisors. The Yongs were outsiders, and so in the new Jianghu of the new Khan, they were allowed a new fiefdom in those northern lands, and spared the violent purge of dissidents and remnant lords.

By the time Min-Na was born, the Yongs had lived and ruled in northern lands for more than a century. When the Tartars’ dynasty fell, and the emperor’s throne became empty, new lords and new generals rose to take the crown for themselves. And they had said it was for freedom. No longer would the cruel Tartar horde oppress and exploit them. The Jianghese would reclaim their lands and freedom, and cast off the yoke of foreign imperialism.

They did not come for the Yongs, at least not at first. At first, it was simply the Tartars, the Tur, the Persians, the Augustines and Soudanians who had come to live in the new Tartar empire. But as the purges grew, the line between what was just and Jianghese and what was foul and foreign grew more and more restrictive, and the Yongs’ position grew more and more tenuous. Although the Yongs were Jianghese, they were also Yeshuan, and they had remained in power even at the height of Tartar rule. The Yongs were outsiders, and so when Min-Na’s father was arrested for treason, the family guard was prepared.

When faced with the Tartar horde, the Yongs had found themselves with no land left to flee to. And so, when faced with the new threat of a new empire, the Yongs fled to the sea. Min-Na and her noble entourage slipped silently into the océan, to make their way to the island of Mompracem. It was a small and isolated region of the Golden Chain, Nusantara, where no Jianghese bureaucrat or bounty hunter would dare to tread. The Khan had tried to conquer Nusantara many years ago, and while his horsemen had proved ill-suited for naval warfare, it provided a home for those Jianghese fleeing the new regime.

That was where Min-Na had grown up, among the supplanted creoles of Nusantara, and for many years that which remained of her family knew peace. But there was always the chance, her guard warned her, that an old score would have want to be settled, or the new emperor would turn his gaze northward just as the Khan had. So as Min-Na grew she trained, learning all the martial arts her family had passed down for generations, and growing into a fine woman warrior.

“Hey.”

The presence of warm, gentle hands on her shoulders stirred Min-Na from her reminiscences, and as she turned she felt a tender kiss place itself upon her cheek.

“Hi,” she smiled as she saw Yann, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed in greeting to the new day.

“Do you miss it?” Yann asked, as he gazed at the Cantonese fields in the distance.

Min-Na peered across the land, trying to locate her old home, but then noticed the hand that held her own, and found herself content.

“Of course,” she said. “But you know, I lived more of my life in Mompracem than I did in Jianghu. I’m like Santama, something that doesn’t fit into a single, neat category.”

“I know what you mean,” Yann smiled. “Like Commodore Zheng, eh?”

Min-Na grinned as she and Yann remembered the adventure that had brought them together. Yann had just arrived in Santama, and was working along the docks when the Jianghese commodore made port at Canton. Pirates had been ravaging the Cantonese coast, and the commodore had been sent with a division of junks to take care of the situation. Yann, then no stranger to seafaring, asked the commodore if he could join the voyage. If the pirates are a plague upon Canton, then surely they are as much a plague on Santama, and it is as much our duty to fight them as it is yours, he said. The commodore laughed at such youthful idealism, but did not protest, and so Yann began work on the Jianghese junk.

Yanez Lobo became Huang Lang, Yellow Wolf, onboard that vessel. But then a storm rendered the division divided, and left Yann shipwrecked on Mompracem. By terrible coincidence, it was soon revealed that the imperial intendant, sent by Tienking to oversee the expedition, was plotting revenge upon the Yong family who had wronged him and fled to Nusantara years ago. Many a twist and turn was dealt as Yann and Min-Na had found each other, but in the end, justice was triumphant, and the treacherous intendant returned to Tienking in chains.

As for the Yong family, they were still officially fugitives. But Commodore Zheng assured them that, with their title long ago exchanged, and the only grudge-holder to face imprisonment, so long as they did not try to take their lands or title back, no-one would challenge their walking freely in Jianghese lands again. At that, some eagerly took the chance to return. Others preferred to stay in their new home of Mompracem. And as for Min-Na, she and Yann had fallen in love, and so they returned to Santama to be wed and live happily ever after.

In less than a week, Min-Na mused, she and her wolf would be married. Neither of them had been born in this factory, and yet together they had made it their home. Together, they were happy, Min-Na knew. So why, as she looked upon her lover’s face, did her wolf seem so dour?

“Is it your father?” she asked.

Yann blinked in surprise, before sighing in affirmation. “Am I that obvious?”

“I’ve just known you long enough,” Min-Na replied.

“I suspected he’d be like this,” Yann leaned against the balcony glumly. “He hasn’t changed a bit, and he’s too long in the tooth to change anytime soon.”

“But you still love him.”

“I… yes… I mean…” Yann sighed. “It’s complicated.”

“Not really,” Min-Na said. “Look at us, or even Santama itself. People can be more than one thing. And you can love the father who raised you, taught you, and loved you. Even if you hate the father who traded in slaves.”

“He did more than just trade in them,” Yann shuddered.

“And you found your brothers and sisters,” Min-Na reminded him. “Every last one of them. And if they’re like João, they’ve found their own happy endings.”

Yann smiled as he remembered João, the last of his brothers to be freed. He was now in Mompracem, living happily and healthily, the newest member of the Yong family.

“You don’t have to forgive him, ever, for all the things he’s done, for all that he still believes and holds dear,” Min-Na said. “But you can offer him the chance to attend our wedding, and you can carry on the things he gave you that are worth carrying.”

“I don’t think he’ll come,” Yann said. “Not after how he reacted yesterday.”

“Maybe not,” Min-Na shrugged. “But we’ve done our part. It’s his move now.”

“Spoken like a true strategist,” Yann noted.

“As the scion of a noble house, I was schooled in all the finest arts of war,” Min-Na said in faux-haughtiness.

At that Yann chuckled, before slowly growing more somber.

“Say, Min-Na,” he asked. “Why did you choose me?”

Min-Na stared, surprised, at her lover for a while, before a wistful expression came over her face, and she gazed into the sun-drenched sky.

“Because when we first met, you didn’t know who I was,” she finally answered. “And when you found out, you didn’t care. When I was little, I heard stories about wolves, coming to snatch children away and gobble people up. And I was warned, always, to not draw attention to myself, in case soldiers ever came to take us away. But when you washed up on our shore, you weren’t anything like the stories I had heard. You were a wolf, but you were my wolf, my protector. And thanks to you, and Commodore Zheng, and João, and everyone, my family is free again.”

“I’m the wolf?” Yann chuckled. “If any of us is the mighty hunter, it’s you.”

“Oh?” Min-Na grinned slyly. “Then perhaps you’d better watch yourself around me.”

“I think I can handle myself,” Yann laughed, as Min-Na pounced on him, and the two lovers whiled away the morning hours together.

As Min-Na strolled through the market square, she marveled at how quickly it had taken the vendors to become familiar with her. Already every merchant and shopkeeper knew her by name, and as she shopped for groceries, they greeted and chatted with her pleasantly. Even the old wives who gathered in the square would invite her over now, to exchange a juicy bit of gossip or give her advice on housekeeping or child-rearing. And through it all, she was always met with the same joyous congratulation over her quickly forthcoming nuptials. This was her home, Min-Na knew as she walked the streets. This was the community she had become a part of, and it made her truly happy.

When she noticed Ulisses Lobo sitting lonely and forlorn at the docks, she did not recognize him at first. He looked so ragged and worn out there in the distance, like a crumpled-up, old cloth that had been thrown away. When at last she did recognize his face though, filled with deadened eyes and a sorrowful glower, his pitiable state could not help but bring a touch of sympathy to Min-Na’s heart.

Slowly, she walked over to where the wolf sat alone and called to him gently.

“Senhor Lobo?”

The wolf had been lost in his thoughts, wondering where it had all gone wrong. Maybe if he’d been stricter with Yann growing up, maybe if he’d instilled him with more proper virtues. Yann was his only son, the continuation of his bloodline. Without him, the Lobo clan’s legacy would die. He could not allow that! But how could he prevent his son’s disgrace? This factory, this country, this whole, entire continent was a madhouse! Sick and perverted in its ways, right down to the bone. Even the Lusians here were content to be sheep, instead of mighty wolves.

All these thoughts had been swirling in Ulisses’ head, when at last, a woman’s voice reached into the mire and plucked him free. The wolf blinked and turned his head about, dazedly gazing into nothing until his eyes focused on Min-Na.

“You…” he mumbled.

“Yes, it’s me,” Min-Na reached out a hand. “Look at the state of you! Come on, I’ll take you home. We can get you a nice shower and a hot meal, and you and Yann can have a nice, long chat.”

“Yann…” the wolf whispered. His son…

“Yes,” Min-Na said. “He wants you to attend our wedding, remember. He and I both. Come on, let’s go home.”

“Home…” the wolf seemed perplexed, before suddenly, an intense, animal fury etched itself on his features, and the wolf lunged for the woman’s throat.

“Se-sen-!” Min-Na tried to cry out but the wolf’s mighty fists were wrapped too tightly around her neck.

“You yellow sow!” the wolf howled. “It’s all your fault! You took my son away from me! I’ll kill you, you hear me, KILL YOU!”

Already members of the market crowd had noticed the wolf and the woman, and were rushing over to stop him, but Ulisses didn’t care. His hands were more than powerful enough to break this girl’s neck before they reached him. Then Yann would see. He’d come around, come back to him, back to his father and title and blood.

What Ulisses did not realize though, was that Min-Na was far from an innocent waif. The years of training in Mompracem kicked in as soon as the wolf seized her, and before the crowd even made it there her hands shot up like lightning and tore the wolf’s hands away. Grabbing his wrists, she pulled him in and kneed him in the stomach, and then as he staggered she slugged him so hard he fell into the sea, before she scooped her groceries up and returned to the cheering crowd.

Ulisses sputtered and spat as he slowly sank into the waves. Unbeknownst to Min-Na or any of the crowd, the wolf could not swim. Like most sailors, Ulisses had been taught that should he fall overboard, the captain would not go back for him. When one is in the océan, countless leagues from any land in sight, to swim is only a prolongment of one’s misery. Better to drown quickly, content in the knowledge that there was nothing to be done, than to die slowly with false hope. And so, as the wolf sank deeper and deeper into the sea, he remarked how unjust it was that this should be his death; tossed overboard like garbage, like a slave that had grown sick and threatening to the remaining stock.

And then a hand plunged into the depths, and hoisted the wolf onto the docks, where he coughed and heaved up all the water that had begun to fill his lungs. For several moments the wolf lay gasping and shuddering, too blinded by the water to even notice his savior. But when at last, his breathing returned to normal, and he wiped his eyes dry, he looked at the figure who had saved him, sitting calm and patiently all the while, and gasped when he recognized her face.

“Hello,” Amaria’s eyes twinkled as she grinned at him. She was no longer glowing, but she remained just as ethereal as she had been in the painting, even in such a plain and mortal form.

“You… who are you?” Ulisses gasped.

“Amaria, silly. Don’t you remember what the father said?” she laughed.

“But… you… why can I see you? Why can no-one else see you but me?” the wolf could not understand.

At that, the shing wong placed her finger to her chin in deep contemplation, before slyly grinning and asking “Say, do you remember the story of Aeneas?”

The wolf furrowed his brow. He did, of course, remember the tale. Lusia was the inheritor of Aenea’s legacy, after all. Aeneas, second of the Twelve Valiants, was one of the few survivors of the Ilion War. As the walls of Ilium fell, and Aeneas fled with what few forces he could muster, a prophecy was foretold, that said Aeneas would found a new kingdom, and a new empire even mightier than that of Mycenae. Many trials were faced as Aeneas sailed across the White Sea, from monsters to misdirection to even more warfare and strife. And all the while, Aeneas was led against his will by the winds of fate, never to know any happiness or freedom unless it was approved of by the gods. Even as he founded the city of Aenea, from which the Aenean Empire would spring, he only longed to be free of destiny’s chains. But freedom never came to him. And comprehension did not come to Ulisses. What relevance did such a tale have to his question?

“He sailed all that way, all across the White Sea, all to carry on the legacy of Ilium,” Amaria said. “But in the end, he didn’t make Ilium anew. He made Aenea. He made something new, something uniquely his.”

“What… are you talking about?” Ulisses frowned.

“You still don’t understand,” Amaria sighed, as one would with an obstinate child. “But it’s a lesson I thought you ought to learn. Let me put it to you like this. Your son, he’s your son, isn’t he?”

“Y-yes?”

“Yes!” Amaria grinned. “But he’s also Mary’s son. Children aren’t perfect copies of one parent, you know. They take qualities of both parents, and it takes a village to raise them. There’s a duality, a complexity, to every child, every human being. Because to be human is to create, to make something new. Your child is doing just that. He’s making something new.”

“But… how can he turn his back on all I built? All I made for him?”

“He isn’t. Not all you made, not everything. He still wants to carry on the Lobo name, and he’s still proud to be a Lusian. But he’s also proud to be a Breton, and a Santaman. He had to make room for all those things, so he got rid of the things he felt were unimportant.”

“Unimportant?” Ulisses cried. “How can he believe that?”

“Because that’s just how children are,” Amaria shrugged. “You were once a child yourself, weren’t you?”

“Children need guidance. They need proper discipline,” the wolf hissed. “I never had all the luxuries Yann did. I was too lenient with him, I made him grow soft. He never had to grow up as quickly as I did, but I see now that was a mistake on my part.”

“But he did grow up, and you can’t turn back time. No matter what you say, he isn’t a child anymore, and he still holds many of the lessons you taught close to his heart.”

“But… he…”

“And you know, if he ever has children, which, given how lovey-dovey he is with his bride-to-be, I don’t rule out as a possibility, he’ll have problems just like you did. Things that were near and dear to him will seem alien and unimportant to them. And the cycle will repeat when they have children of their own.”

“But our empire!”

“What is an empire but a collection of people? People having children, going through the cycle of change, on and on, forever and eternity. The Lusia of today is nothing like the Lusia of yesterday, and the Lusia of tomorrow will be nothing like the Lusia of today, because all those people will change as new generations are born.”

“No! I won’t accept it!” the wolf howled. “Our blood, our soil, our reign is eternal! If it isn’t eternal, if it’s doomed to die and decline, then what’s the point of even fighting for it at all?”

“I kinda figured you’d see it that way,” Amaria sighed. “Still, if you’re really so curious, why don’t you ask your son? He’s right there, behind you.”

“What?” Ulisses whipped his head around, to see the crowd that had gathered in congratulation around Min-Na. There, as the guardian angel had said, desperately clutching his fiancée and asking if she was alright, was Yann.

“Yann!” the wolf cried in anguished joy, and the crowd’s attention was drawn back to the old man on the docks.

He had to convince his son, Ulisses knew. He had to make him see reason. This was it. This was his last and only chance. If Yann did not heed his warning now, calamity and ruin would fall upon the house of Lobo, and their clan’s legacy would die. He had to make Yann see!

But before the wolf could say anything more, the son had coldly clasped his lover’s shoulders, and turned his back on his father. Ulisses tried to summon up all the power of his booming voice, to recapture the bellow that had disciplined the child when he had been small and misbehaving. But the wolf saw, as Yann and Min-Na strode further and further away from him, his son was not a child anymore. The wolf could not find his voice.

“Please…” the wolf turned to where Amaria sat, but found she was no longer there. She had disappeared, as though she had never been there to begin with, and the wolf was all alone.