Courage and Cowardice - Chapter 21

The sun was bright and the sky was clear on the day the stranger arrived at Santama.

NOW this is the Law of the Jungle — as old and as true as the sky;

And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.

As the creeper that girdles the tree-trunk the Law runneth forward and back —

For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack.

-The Law of the Jungle

“And with that, the Buddha flung Rei Macaco out of heaven, and dropped a mountain on him, just for good measure. Then, just to be sure, the Buddha placed a heavenly seal on the mountain, which could only be lifted by the prayers of one truly good and pure-hearted, something Rei Macaco was most certainly not.

“‘Ha!’ the gods laughed as they admired the Buddha’s handiwork. ‘That ought to show him!’

“‘Well,’ the Buddha shrugged. ‘We shall see.’

“And with that,” the syutsyu-jan groaned as he lifted himself from his seat. “Our story ends for today. Thank you all for listening, I hope you shall attend tomorrow.”

“No!” a tiny tot cried. “Is that the end? But Rei Macaco lost!”

As the crowd chuckled, the tot’s mother scolded her for shouting such impertinent questions, but the syutsyu-jan simply smiled.

“Now don’t you worry, young one,” the syutsyu-jan assured the child. “That isn’t the end of Rei Macaco. Indeed, it’s only just the beginning of his story!”

“The beginning?” the little one’s eyes widened.

“Yes,” the syutsyu-jan grinned. “Trust me, there’s far more to Rei Macaco’s story than just that. But if you want to hear it, you’ll have to show up tomorrow, alright?”

“Okay!” the tot nodded, before pleading with her mother to let her attend the next of the storyteller’s sessions.

The syutsyu-jan smiled as the crowd dispersed, and all that remained were himself and the amanuensis. The syutsyu-jan gazed at the fellow and grunted to himself. With his lithe, muscular frame and thick, blond hair, he seemed as though a yellow wolf.

“So tell me, son,” the syutsyu-jan asked after the amanuensis had finished his scribblings and thanked him. “Why the interest in writing down my stories?”

Yann blinked at the question, before turning his gaze away somewhat sheepishly.

“Well, it’s just…” he said. “I feel it’s my duty, I suppose.”

“Duty?” the syutsyu-jan raised a brow.

“Yes,” Yann continued, more sure of himself as he went on. “I think… before any empire can truly conquer a people, they first have to subjugate their stories. Either convince the people that they don’t have any real stories at all, or convince them that their stories aren’t as important as the empire’s.

“So, I write down all the stories I can, write them and retell them, because maybe, if I do, they won’t be lost. They’ll survive, and when the empire crumbles, like they always do, people will be able to pull the stories from the rubble, and know that they existed. I know it might sound selfish or self-aggrandizing, but I want to do this, because without it, the stories, the people, their very existence might be lost forever.”

The syutsyu-jan stared at the young man for a while.

“You’re right,” he said softly. Then, with a barking laugh, “That is pretty self-aggrandizing!”

Yann flinched as though the words had been a lightning bolt, but the syutsyu-jan only laughed harder, as he patted the young man on the shoulder in comforting assurance.

“Don’t worry, don’t worry,” he said. “It’s a fine thing, what you’re doing. But remember, even a binding thread is just one thread. You need all the others to make a full and strong chord. No matter how important any storyteller is, they weren’t the first, and they certainly won’t be the last authority on their subject. Remember all who came before you, and make room for all who’ll come after you.”

“Y-yes sir,” Yann had recovered from his shock, and was now bowing graciously in thanks for the lesson. “Thank you.”

“Not at all,” the syutsyu-jan laughed. “Just remember to attend tomorrow’s session. I wasn’t lying when I said Rei Macaco’s story had just begun.”

“Yes sir!” Yann grinned.

“And neither has yours,” the storyteller said.

The sun was bright and the sky was clear on the day the stranger arrived at Santama. Thanking the captain for his generous hospitality, the stranger left the ship to stroll along the docks. There were many people gathered there that day, but as the stranger made it into the market square he found several shopkeepers absent, their posts taken by proxies and regents. It was a wedding day, the stranger learned, and the people familiar to the bride and groom wished to attend. The stranger understood, and made sure to buy a few trinkets before making his way to the church. It would surely please the shopkeepers to see their absence had not affected their bottom line too greatly.

As the stranger continued his stroll, he noticed a girl, swinging her legs from the railing where she sat. She was young, far, far younger than he, and yet she was of a similar substance and form. The stranger made sure to bow in polite deference to the girl, as he could tell it was her that he now walked in, and she in turn bowed and giggled in excited glee. To have such an honored guest was truly a pleasure. As she hopped down from the railing, she asked what had brought the stranger to her, and if she might make his stay more pleasant. The stranger spoke no words, but conveyed his thanks, and assured the girl that he needed no red carpet or royal welcome. He was content to simply walk, to see what sights might cross his path, and follow what paths might present themselves to him.

As the stranger had understood it, there was to be a wedding that day. And so, glad to be of assistance, the girl directed the stranger down the path most suitable for finding the appropriate church. Speed was less important to the stranger than pleasantry, and so the girl made sure to tell him of several choice landmarks he would see as he walked along her roads. The stranger was most thankful for the girl’s aid, and played her a song in show of his gratitude, at which she danced and clapped with glee.

The walk was pleasant, and the stranger took the time to marvel at the many sights he saw. When last he had walked these lands, no factory had existed, and he wondered if, when next he arrived on this Cantonese shore, such a city would still be standing. The stranger had seen many a city rise and fall, seen many of his brethren grow old and die. And yet, their kind always endured. Even when the walls fell and the buildings crumbled, the idea, the story of the place, would continue. And so long as men dreamed, the stranger and his kind would never truly die.

By the time the stranger made it to the church, the crowd had gathered by the entrance with rice ready and smiles on their lips. Still, the stranger could get a good view of the spectacle from the shade of a nearby tree. It seemed like an ideal spot, as there was already an old and tired wolf sitting forlornly in its shadow. The wolf seemed in great despair, with his hair all matted and his clothes all ripped and rumpled. But to the stranger he was as good a companion as any, and even as the wolf was too intent on the sight before him to notice, the stranger sat down beside him, and took the opportunity to adjust his lute strings.

There, accompanied by the cheers and roaring of the crowd, the bride and groom exited the church doors. The rice fell as rain, as a sign of prosperity and good fortune, and the newlywed couple laughed and cried in jubilation. The stranger, shaking his head as he grinned from ear-to-ear, clapped the wolf’s shoulder in congratulations. The wolf did not react at first, but when at last realization sank in, the wolf slowly turned his head in curiosity, before the sight of the stranger sent his already-pale face into ghostly apoplexy.

“You-!” the wolf choked, but the stranger urged the wolf to calm himself. It was true, the resemblance was uncanny, but, as the stranger’s golden eyes twinkled, so differently from the groom’s océan blue, it was also, he assured the wolf, purely coincidental. And besides, the stranger pointed one finger to his smiling lips and another into the distance, there were others who warranted the wolf’s attention.

As the wolf turned back he saw that the bride and groom had noticed him, so far away from the regular guests. The wolf opened his mouth again and again, but no sound came out. Even so, whatever words he could have spoken, it seemed the couple understood, and as their faces remained neutral, a short, polite nod from the groom was all the response the wolf got, before the couple returned to their march. The wolf slumped; he was so exhausted. But the stranger gave a heartening clap on his back, and encouraged the wolf to keep his spirits up. After all, tomorrow was another day.

Suddenly a wind whistled through the air, and the stranger grew oddly alert. Was it that time already? He had been expecting it, hence his journey to this city, and yet he had not expected it so soon. Still, he was close, and could even make it on foot, if he was quick about it. And so, with an apologetic bow, the stranger slung his lute over his shoulder and bade the wolf adieu. The wolf pressed the stranger, curious as to the cause of his departure, but the stranger assured him, it was a matter of utmost urgency. There was a promise that had to be kept, and the stranger always kept his promises.

In the church’s sacristy, the youth helped the father put away his officiating vestments. The father had wed many a couple in his time, but found himself unusually tired after today’s ceremony. He found himself struggling to keep his eyes open, and he asked the youth to help him to his bed. The youth expressed concern, but the father simply laughed and told him not to worry. He was only a little fatigued, and an afternoon nap was all that he required. The youth still seemed unsure, but did as he had been asked, making sure to hold the father’s hands as his creaking limbs hobbled into the little room where he always slept. Tucking the father into bed, the youth asked if there was anything he still required, and when no such orders were relayed, he left the father to his peaceful slumber.

When a figure slipped into the window, blocking the sunlight seeping in and disturbing the father’s dozing, the father at first thought it to be the youth returning. But as the stranger made his way to the father, his hair and eyes glowing just as golden as the day they had first met, the father knew that the day had come.

“You…” the father whispered, a warm, contented feeling bubbling from his soul. After all this time, at last. The father had almost started to give up hope, but there, exactly as the father remembered him, the stranger stood. The stranger reached out to gently clasp the father’s hand, and patted it in apologetic sympathy. It had been quite some time since their first meeting, and the stranger did not begrudge the father if he felt somewhat upset. But the father assured the stranger, he felt not one whit of anger or resentment. The stranger had come, after all, just as the father had hoped, and that was all he could have ever asked for.

Of course, the stranger pondered how best to gently broach the subject, but before he could continue the father assured him of his knowing. It was not difficult to guess the reason for the stranger’s return, and the father did not begrudge him one bit. His life had been long, and filled with laughter and love, even with all the pain and loss that joined it. No life is ever solely joyful or solely sad, and the father’s was no exception to this rule. He was content, and had no regrets, though perhaps…

The youth, the father remembered him. What would become of him, after the father’s departure? At that, the stranger assured him, he had no cause to worry. The stranger would look after him, and make sure that he found the peace he sought. That was good, the father relaxed. In such hands as the stranger’s the father knew that the youth would be well looked after. And if that were so, then there were no other earthly matters the father had left to attend. He was ready.

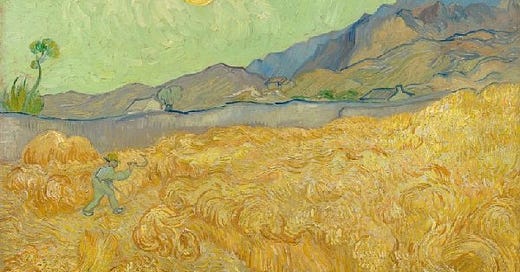

So, as the father lay gently back down to sleep, the stranger allowed him a detour, before he reached his final resting place. Again, the stranger let the father walk along his winding paths, touch the golden wheat of his fields, taste the crisp and fertile air of his sky, and hear the song of his gentle wind.

A lute song guided the father on his journey, until at last, he found his way, and left the stranger for good.